Transcript

What do the gospels say directly about being gay? Keep watching to find out.

OK, so here is everything the gospels say directly about being gay.

Sorry – that’s it. The gospels say nothing directly about being gay.

Now, there’s plenty in the gospels which speaks indirectly – but that’s not the focus of this video.

People on both sides of the issue argue that the gospels do speak pretty directly about being gay, so why do I disagree?

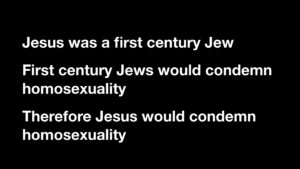

Those on the non-affirming side sometimes argue: Jesus was a first century Jew, any first century Jew would condemn homosexuality, therefore Jesus would and does condemn homosexuality.

Those on the non-affirming side sometimes argue: Jesus was a first century Jew, any first century Jew would condemn homosexuality, therefore Jesus would and does condemn homosexuality.

Yes, but Jesus isn’t just any first century Jew – he’s different, he’s God, without that we don’t have Christianity, we don’t have the gospels. So this type of logic, this type of argument isn’t particularly helpful.

Then there’s arguments from silence. Those on the affirming side sometimes argue, ‘Jesus didn’t say anything against homosexuality, he didn’t condemn it, and therefore it must be OK’. Well, there are loads of things we don’t have a record of Jesus condemning including slavery. It doesn’t necessarily make them right.

But those on the non-affirming side sometimes argue, ‘the reason Jesus said nothing about was because it would have been so obvious to all around that it was wrong that it didn’t need saying’. Which is equally just pure speculation. We are in danger here of filling the silence with our own presuppositions.

OK, there are also arguments which depend on particular passages which, people on both sides claim, show what Jesus thought about homosexuality. These are the passages where Jesus talks about marriage, where Jesus talks about sexual immorality, and where Jesus heals a centurion’s slave.

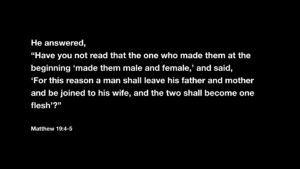

First of all let’s look at Jesus talking about marriage. The passage comes from Matthew 19 (there is a similar account in Mark 10). Jesus is asked how easy divorce should be. This was a current debate – one school of thought arguing that a man should be able to divorce his wife for any reason at all, whereas another school argued that he should only be able to divorce her in cases of sexual immorality.

First of all let’s look at Jesus talking about marriage. The passage comes from Matthew 19 (there is a similar account in Mark 10). Jesus is asked how easy divorce should be. This was a current debate – one school of thought arguing that a man should be able to divorce his wife for any reason at all, whereas another school argued that he should only be able to divorce her in cases of sexual immorality.

Jesus responds by going back to the account in Genesis: God made them male and female; for this reason a man shall leave his father and his mother and be joined to his wife, and the two shall become one flesh.

Let us be absolutely clear here – Jesus is addressing the permanence of marriage, not who you can marry. Of course Jesus talks about male and female – both he and his hearers lived in a world where that’s who got married. In contrast, and in particular in Judaism at the time, same-sex marriage would not have been even a glimmer on the horizon of their conversation.

So the passage addresses directly whether marriage should be lifelong, not whether same-sex marriages can be honouring to God. Jesus strongly affirms traditional marriage, but he doesn’t therefore condemn all alternatives, including celibacy.

The passage does not deal with same-sex marriage, and any attempts to make it so are arguing, again speculatively, from silence.

These verses need careful unpacking and handling. Many protestant churches hold that, in certain circumstances, remarriage after divorce is possible, and I agree with that.

These verses need careful unpacking and handling. Many protestant churches hold that, in certain circumstances, remarriage after divorce is possible, and I agree with that.

But you can’t go from nuanced interpretations about the permanence of marriage, which the passage addresses directly, and then use the same passage as a blunt instrument to condemn same-sex marriage, which the passage doesn’t address directly. It smacks of double standards.

The second passage that you may hear used comes from Mark 7. Jesus proclaims that it is not what goes into your body that defiles you, it is what comes from your heart: ‘For it is from within, from the human heart, that evil intentions come: fornication, theft, murder, adultery, avarice, wickedness, deceit, licentiousness, envy, slander, pride, folly.’

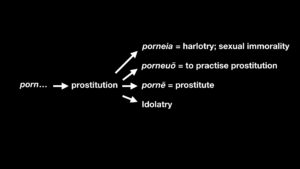

The Greek word translated as ‘fornication’ is porneiai – sexual immoralities. It’s where we get words like ‘pornography’ from. Some people have argued (and it ended up in an official Church of England document) that this plural form – porneiai – would immediately lead any first Century Jew to think of the list of forbidden offences in Leviticus 18 and 20, which include things like incest, bestiality, adultery, and male same-sex intercourse. [See Gagnon 191-193; Paul 19; see also Some Issues in Human Sexuality 145].

This is wrong. First of all, there is no particular significance in the word being plural. All the sins mentioned in the list are plural. It’s actually sexual immoralities, murders, adulteries, and so on. And that makes sense because Jesus is talking about the evil intentions, plural, that come from the heart.

Secondly, a bit more on the word porneia (the singular form). It comes from the root porn – which refers to prostitution. So the word porneia would evoke sleeping with prostitutes in particular, or sleeping around more generally. It was also used within Judaism to refer metaphorically to idolatry.

Secondly, a bit more on the word porneia (the singular form). It comes from the root porn – which refers to prostitution. So the word porneia would evoke sleeping with prostitutes in particular, or sleeping around more generally. It was also used within Judaism to refer metaphorically to idolatry.

Why does Jesus add this and adultery? Because adultery was, legally, only sleeping with someone else’s wife. Sleeping with a prostitute or a slave was not legally adultery. So Jesus is saying, evil intentions include sleeping with other people’s wives – adultery, or sleeping around more generally – porneia.

The term porneia or its Hebrew equivalent [z’nut] weren’t generally used by the rabbis when they talked about these sections of Leviticus, and in fact some of the offences are specifically designated as not being porneia. So no-one listening to Jesus, or listening to the gospel when it was first written, would have thought that Jesus was referring to homosexuality.

So neither of these passages address our issue – loving, faithful, committed same-sex relationships. But what about the centurion’s servant? This is sometimes presented as Jesus healing a gay centurion’s lover.

The background to this is that Roman soldiers weren’t allowed to marry whilst on active service; they had to wait until they retired. It was not uncommon for senior military officers (like a centurion) to have slaves including boys, and sometimes to use the boy slaves for intercourse.

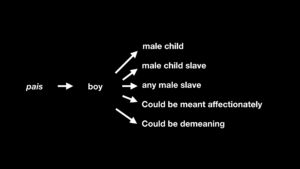

In Luke 7 we are told of a centurion in Capernaum, who has a highly valued slave close to death. The centurion asks Jesus to heal from a distance, trusting in Jesus’ authority, and saying ‘but only speak the word, and my boy – in Greek pais – shall be healed’.

The word pais here can have multiple meanings – the slave may well have been a boy, but, just as in the antebellum South in America, ‘boy’ could mean any male slave.

The word pais here can have multiple meanings – the slave may well have been a boy, but, just as in the antebellum South in America, ‘boy’ could mean any male slave.

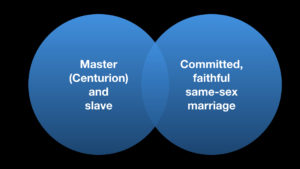

So was this a gay centurion asking for healing for his lover? And does Jesus praising the centurion mean that he accepted gay relationships?

I think that’s reading too much into the passage in a number of ways. First, whilst it is historically plausible that the centurion was using his slave for intercourse, it is equally plausible he wasn’t. Luke doesn’t say enough for us to be able to tell.

Secondly, even if he were, that doesn’t mean that the centurion was gay. I’m going to cover this more in future videos, but the ancient world didn’t categorise sexuality by who you had sex with, but whether you were the active, dominant partner or the passive, submissive partner.

So the same man might have intercourse with a boy slave, with a female prostitute, and then with his wife, and the ancient Roman world would have seen that as perfectly normal and acceptable.

This centurion might have been using a boy slave, but might equally have been then expecting to marry on retirement from the army.

And thirdly, this is not a relationship that I want to appeal to or hold up anyway.

And thirdly, this is not a relationship that I want to appeal to or hold up anyway.

It is not consensual, it is master-slave, it is inherently abusive. And so it is completely different to the type of relationships that we are talking about: committed, faithful, loving, same-sex relationships.

Conclusion

Don’t get me wrong. I think there is much in the gospels which speaks indirectly about this issue. But, there is nothing in the gospels which speaks directly about being gay.

There’s more videos coming, so subscribe to the channel, and you can find more resources at www.bibleandhomosexuality.org.

The main passages in the New Testament that usually come up with sexuality are in Paul’s letters. Perhaps the most important is Romans 1 – you can read my explanation on this page.

Found this helpful? You can now get the material from this website and more in a book. Affirmative: Why You Can Say Yes to the Bible and Yes to LGBTQI+ People is available at Amazon and other major retailers. You can find out some more about the book here.

Resources

The root of the argument that porneiai in Mark 7:21-23 refers to Levitical offences appears to come from Gagnon, 191-93. For a relatively full response, see in particular Haller, 125-134. A fairly comprehensive account of the development of the term porneia was provided by Harper. However, note that Glancy has argued that intercourse with one’s own slaves would not necessarily have been seen by Jewish males as porneia.

Gagnon, Robert A. J. The Bible and Homosexual Practice: Texts and Hermeneutics. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 2001.

Glancy, Jennifer A. “The Sexual Use of Slaves: A Response to Kyle Harper on Jewish and Christian Porneia.” Journal of Biblical Literature 134, no. 1 (2015): 215-29.

Haller, Tobias Stanislaus. Reasonable and Holy: Engaging Same-Sexuality. New York: Seabury Books, 2009.

Harper, Kyle. “Porneia: The Making of a Christian Sexual Norm.” Journal of Biblical Literature 131, no. 2 (2012): 363-83.

For a similar perspective to mine on the nature of the relationship between the centurion and his slave, see the post A Centurion and his “Lover”: a Text of Queer Terror by Christopher Zeichmann. He has also addressed other aspects of this pericope in:

Zeichmann, Christopher B. “Rethinking the Gay Centurion: Sexual Exceptionalism, National Exceptionalism in Readings of Matt. 8:5-13//Luke 7:1-10.” The Bible and Critical Theory 11 (2015): 35-54.